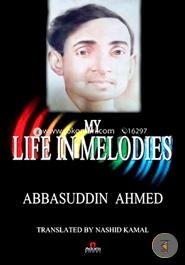

আব্বাস উদ্দীন আহমদ

Abbasuddin Ahmed was born on October 27, 1901 in the then Cooch Behar, in a fairly typical conservative Muslim family and all the traits of a Muslim village boy were embedded in his upbringing. From a very early age, Abbasuddin had a deeply religious bent of mind and at the same time he showed signs of being a lover of music. He was never trained in any formal music school; his musical alma mater was the school of nature. He wrote in his autobiography Amar Shilpi Jeeboner Katha that the first sounds that he was initiated into were those of the chirping birds, the sounds of the flowing monsoon waterfalls, the ringing of the school bell, etc. He set off for Calcutta in search of a living and for fame in music. His first song was recorded with the assistance of Prof. Bimal Dasgupta who was working with His Master\\\'s Voice, HMV for short, and whose father was a teacher of Jenkins School, Cooch Behar. That was the late twenties and in those days, no other Muslim singer used his own name on the label of the record, lest the elite community of Kolkata frown upon the audacity of a Muslim boy trying to get a position in a field which was their special preserve. An artiste of the stature of Kasem Mullick used a pseudonym K. Mullick to sound non-Muslim. Music and its practice were unknown to the Muslim Bengali homes. It was considered to be more of a Hindu tradition to pursue arts like vocal music, dance, painting and the like. To the consternation of HMV, Abbasuddin insisted on using his own Muslin name on the label of gramophone records and had his way, in spite of the lifting of many eyebrows. Abbasuddin recorded two songs on two sides of a record, one written by his friend, the famous composer Shailen Roy and, the other, also by a friend of his, Jiten Moitra. Sensing his potential, HMV asked Abbasuddin to record eight more songs in one go. Prof. Bimal Dasgupta advised him against it. He knew it was a ploy by the company to record ten songs in one go and thereby attain copyrights, putting away the artiste with a paltry one-off payment. Rightly enough, the first two songs \\\'Kon birohir nayan jole badol jhare go\\\' and \\\'Sharan parer ogo priyo\\\' became very popular and Abbasuddin was asked to record again and again. After he gained some name and fame through his first few records of modern Bengali songs and through memorable rousing performances at Calcutta\\\'s proverbial musical soirees on umpteen occasions, Abbasuddin met his idol, poet Kazi Nazrul Islam. By then Abbasuddin had created a niche for himself in the musical world of Calcutta. Nazrul wrote songs for him, mostly modern Bengali songs like \\\'Ashibey tumi jani priyo\\\', or \\\'Snigdha shyam beni barna\\\', all of which were received by the record purchasing community of the then Bengal with warm appreciation. Abbasuddin\\\'s name emanated a glory that a Muslim singer had never known before. Abbasuddin pleaded with poet Kazi Nazrul Islam, his Kazida, that the Hindus had many of their songs in Bengali written for their festivals like Holi, Durga Puja, Swaraswati Puja etc. while the Muslims had none. Kazida agreed and after overcoming the initial stiff refusal of HMV, this joint venture resulted in the next record with the songs on Eid: \\\'O mon, ramjaner oi rojar sheshey elo khushir Eid\\\'. This and other Islamic songs had an electrifying effect on both Hindu and Muslim ears, due to their universality, novelty and unique renderings by Abbasuddin. Even those whose religious inclinations were a total non-acceptance of music in any form, found those Islamic songs to be extremely resonant of their deepest spiritual yearnings. So music entered the Muslim homes in a religious-cultural garb. Music found much more lavish welcome than it could have obtained otherwise. Moreover, each Muslim religious occasion could find befitting songs from the never-to-be-beaten pen and musical compositions of Nazrul to celebrate and commemorate. Many more songs were recorded during this period. \\\'Allahte jar purna iman\\\', \\\'Jage na shey josh loye aar Mussalman\\\', \\\'Towfiq dao Khoda Islame\\\', \\\'Bajichey damama bandhrey amama\\\' are just a few titles of these innumerable songs. On almost every Islamic occasion such as the Muharram, the birth of the Prophet, the Eid-ul-Fitr, the Eid-ul-Azha, Nazrul\\\'s songs were sung. The triumphant duo - Kazi Nazrul Islam and Abbasuddin Ahmed - were considered pioneers in the field of infiltrating culture into Muslim homes by lifting the taboo of music. Poet Ghulam Mustafa too played a pivotal role during this period. Himself a composer and singer, he composed a number of songs for Abbasuddin, which Abbasuddin sometimes sang solo in the records, sometimes in duet with Ghulam Mustafa. Ghulam Mustafa himself recorded a few Islamic songs in his own voice. During this time, the late 30s and early 40s, the great statesman A.K. Fazlul Haque rose to eminence. He initiated Abbasuddin to sing for his huge audience during his political meets. Abbasuddin was now at the peak of his popularity. But his artistic soul still remained dissatisfied. He wanted to record the songs of the rural sons of the soil from whom he rose and bring into limelight the treasures of folk literature and music. All this was till then unknown to the elite community of Bengal. In this he was helped by poet Jasimuddin who was waiting for a right voice for the listeners to hear what he had stored in his rich collection and in his own inimitable compositions. This folk duo - Abbasuddin and Jasimuddin - opened up a new horizon of music. \\\'Nadir kul nai kinar nairey\\\', \\\' O tui jare aghat hunley rey maney\\\', \\\'Prana shakhire oi shon kadambatalay\\\', `Amar har kala karlam rey\\\', to mention only a few, filled the air of rural and urban Bengal with an ecstasy and freshness never before heard of in the annals of musical history of Bengal. Abbasuddin had still an unfinished agenda. Bhawaiya songs, the cradle of which is Cooch Behar, his native home, was engrained in his musical veins. Bhawaiya, Khirol, Chatka and other varieties of folk songs are written in North Bengal dialect and sung in a long drawn-out melancholy tone, the voice breaking at points. These varieties of music are North Bengal\\\'s own, especially of Cooch Behar and the greater Rangpur district. These songs are also sung in the accompaniment of dotara, but the dotara\\\'s strings are made of Muga thread, not of metal strings and is played differently, with opposite strokes, called ulta dhung. Abbasuddin requested HMV to allow him to record Bhawaiya. He was spurned and told that regional songs wouldn\\\'t have a market. But Abbasuddin\\\'s records put HMV on a sound economic footing and his request could not be put off for long. Again the beginning was a compromise, Bhawaiya tune and elite language \\\'Nadir nam shoi anjana\\\' and \\\'Poddo dighir dhare dhare oi’. These songs written by Nazrul Islam (shadowing the original bhawaiya tune) led to a record sale of the disc. It was then the turn of the HMV to request Abbasuddin to record a few more of these. Abbasuddin now played his card and insisted on pure Bhawaiya. The company agreed and came an avalanche of well chosen, almost classical masterpieces, yet unparalleled for their eternal beauty. \\\'Phande pariya baga kandey rey\\\', \\\'Oki garial bhai\\\', \\\'Ki o bandhu Kajal bhomora rey\\\', \\\'Kisher mor randhan, kisher more baran\\\', \\\'Oki ekbar ashia shonar chand\\\' and many other bhawaiya songs crossed the frontiers of North Bengal and came to occupy a place of pride by the side of other varieties of folk music like bhatiali, marfati, murshidi, jari, sari, dehatattya, bichhedi, etc. which Abbasuddin himself amassed in his rich repertoire of records. Abbasuddin took active part in the upheaval that continued in the then British India. No political meeting was complete without his songs. He carried his torch of firmness and truth and sang his hair-raising songs to boost the morale of the teeming millions. In doing so, he encountered grave danger. Risking his life he motored his way through the riot -ridden areas of Calcutta, recording the first song on Pakistan \\\'Shakal desher cheye piara\\\', written by poet Ghulam Mustafa. The non-Muslim accompanists refused to play their instruments in a song on Pakistan. So he borrowed the services of a European instrumental band the Casanova. He opted for Pakistan and came to Dhaka in July 1947 where he settled with his family. The Dhaka Radio Station celebrated the birth of Pakistan on the 14th August 1947 with a recitation from the Holy Quran, and the next item on the ether of the independent nation was that of Abbasuddin. He sang \\\'Shakal desher cheye piara\\\', the first recorded song on Pakistan. In the early morning of 14th August, 1947 he roused the sleeping city of Dhaka singing with his sonorous voice that song on Pakistan, being driven in an open jeep with a microphone in hand. Later he traveled far and wide representing his country in music. It was about the mid-50s, Abbasuddin was suffering from a very serious incurable disease for which he sought medical consultation in UK. The doctors professed not knowing any remedy to his illness and Abbasuddin arrived back in Dhaka only to suffer further aggravation of his illness. He tried to face his illness with great strength and courage. Abbasuddin was a source of joy to all around him. He encouraged the debut and growth of other artistes who followed him, like Late Abdul Halim Chowdhury, Late Bedaruddin Ahmed, Sohrab Hossain, Late Abdul Latif, Late Abdul Alim, Late Momtaz Ali Khan, Late Md. Osman Khan and others who acknowledged their debts to him with heart-felt gratitude. He paved the way for new female singers like Feroza Begum and Laila Arjumand Banu. His house at Purana Paltan at Dhaka was more like a cultural center where cultural personalities like Begum Sufia Kamal, Zubeda Khatun, Jahanara Arzu came for cultural interaction, to celebrate the 1st of Baisakh, to read out their poems or sing their songs, or just to meet and talk to him. During his illness, Abbasuddin wrote his autobiography Amar Shilpi Jeeboner Katha. He gave great strength to his three children, former Chief Justice Mustafa Kamal, Mustafa Zaman Abbassi and Ferdausi Rahman, to remember the greater cause in life and not to be lost in the process. He was vibrant, alive and a friendly guide to the children. He not only left behind a legacy of rich music but he also taught them how to discipline themselves, to carry on the legacy, and attain more. Abbasuddin left this mortal world on the 30th December, 1959. Until September, he had the strength to write his own dairy. On 26th September (1959) he wrote: \\\"After a few days when I will leave this earth, the whole world will forget me. Only the sun, the moon and the stars will be there forever and will guard the earth. The westerly winds, the chirping of the birds, the water in the rivers and the sweet perfume of various flowers in my garden and in those of others will remain. These will blossom, wither away and blossom again. I had blossomed, I had laughed for a while, I am now withering away. I will wither away, but will not blossom again\\\". What Abbasuddin did not know was that he had blossomed forever. In the minds of the Bengalis his sweet fragrance is never to wither, only to grow stronger with the passage of time. As his songs are heard again and again, the soul of Abbasuddin is passed on from one generation to another. (Dr. Nashid Kamal)

![]()

Hello, Sign in

Hello, Sign in

Cart

Cart