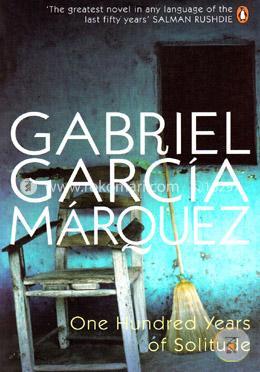

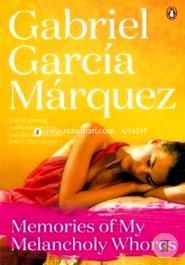

গাব্রিয়েল গার্সিয়া মার্কেস ১৯২৭ সালে কলোম্বিয়ার আরাকাতাকায় জন্মগ্রহন করেন। তিনি বোগোতা বিশ্ববিদ্যালয়ে পড়াশোনা করেন এবং পরবর্তীকালে তিনি কলোম্বিয়ার এল এস্পেক্তাদর সংবাদপত্রের রোম, প্যারিস, বার্সেলোনা, কারাকাস ও নিউ ইয়র্কের বৈদেশিক সংবাদদাতা হিসাবে কাজ করেন। তিনি বেশ কয়েকটি উপন্যাস ও গল্পগ্রন্থের রচয়িতা, তার মধ্যে বিশেষভাবে উল্লেখযোগ্য হল: আইজ অব আ ব্লু ডগ (১৯৪৭), লিফ স্টর্ম (১৯৫৫), নো ওয়ান রাইটস টু দ্য কর্নেল (১৯৫৮), ইন ইভিল আওয়ার (১৯৬২), বিগ মামা’স ফিউনারেল (১৯৬২), ওয়ান হান্ড্রেড ইয়ার্স অব সলিচুড (১৯৬৭), ইনোসেন্ট এরেন্দিরা এ্যান্ড আদার স্টোরিজ (১৯৭২), দ্য অটাম অব দ্য প্যাট্রিয়ার্ক (১৯৭৫), ক্রনিকল অব আ ডেথ ফরটোল্ড (১৯৮১), লাভ ইন দ্য টাইম অব কলেরা (১৯৮৫), দ্য জেনারেল ইন হিজ ল্যাবেরিন্থ (১৯৮৯), স্ট্রেঞ্জ পিলগ্রিমস (১৯৯২), অব লাভ এ্যান্ড আদার ডেমনস (১৯৯৪) এবং মেমোরিজ অব মাই মেলানকলি হোরস (২০০৫)। দীর্ঘ রোগভোগের পর গাব্রিয়েল গার্সিয়া মার্কেস ১৭ এপ্রিল ২০১৪ সালে প্রয়াত হন। Gabriel José de la Concordia García Márquez (6 March 1927 – 17 April 2014) was a Colombian novelist, short-story writer, screenwriter and journalist, known affectionately as Gaboor Gabito throughout Latin America. Considered one of the most significant authors of the 20th century and one of the best in the Spanish language, he was awarded the 1972 Neustadt International Prize for Literature and the 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature. He pursued a self-directed education that resulted in his leaving law school for a career in journalism. From early on, he showed no inhibitions in his criticism of Colombian and foreign politics. In 1958, he married Mercedes Barcha; they had two sons, Rodrigo and Gonzalo. García Márquez started as a journalist, and wrote many acclaimed non-fiction works and short stories, but is best known for his novels, such as One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975), and Love in the Time of Cholera (1985). His works have achieved significant critical acclaim and widespread commercial success, most notably for popularizing a literary style labeled as magic realism, which uses magical elements and events in otherwise ordinary and realistic situations. Some of his works are set in a fictional village called Macondo (the town mainly inspired by his birthplace Aracataca), and most of them explore the theme of solitude. On his death in April 2014, Juan Manuel Santos, the President of Colombia, described him as "the greatest Colombian who ever lived."

![]()

Hello, Sign in

Hello, Sign in

Cart

Cart