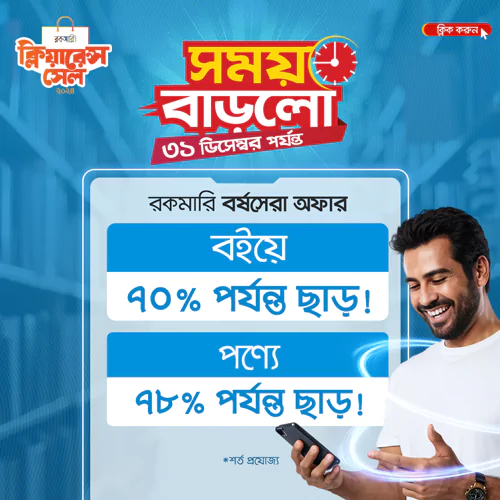

Welcome to Rokomari.com!

Recently searched ![]()

Popular right now

পদার্থবিজ্ঞান রসায়ন জীববিজ্ঞান উচ্চতর গণিত অর্থনীতি পৌরনীতি ইতিহাস ইসলামের ইতিহাস উৎপাদন ব্যবস্থাপনা ও বিপণন ফিন্যান্স, ব্যাংকিং ও বিমা হিসাববিজ্ঞান ব্যবসায় সংগঠন ও ব্যবস্থাপনা ভর্তি প্রস্তুতি রিচার্জেবল ফ্যান ছাতা ইসলামি বই বিসিএস, ব্যাংক ও সরকারি নিয়োগ প্রস্তুতি মোটিভেশনাল বই বিশ্ববিদ্যালয়, মেডিকেল ও ইঞ্জিনিয়ারিং ভর্তি প্রস্তুতি Organic Food উপন্যাস ফ্রিল্যান্সিং ও প্রোগ্রামিং Calculator বইমেলা ২০২৪ Watch Groceries

Hello, Sign in

Hello, Sign in

Cart

Cart