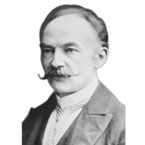

One of the most renowned poets and novelists in English literary history, Thomas Hardy was born in 1840 in the English village of Higher Bockhampton in the county of Dorset. He died in 1928 at Max Gate, a house he built for himself and his first wife, Emma Lavinia Gifford, in Dorchester, a few miles from his birthplace. Hardy’s youth was influenced by the musicality of his father, a stonemason and fiddler, and his mother, Jemima Hand Hardy, often described as the real guiding star of Hardy’s early life. Though he was an architectural apprentice in London, and spent time there each year until his late 70s, Dorset provided Hardy with material for his fiction and poetry. One of the poorest and most backward of the counties, rural life in Dorset had changed little in hundreds of years, which Hardy explored through the rustic characters in many of his novels. Strongly identifying himself and his work with Dorset, Hardy saw himself as a successor to the Dorset dialect poet William Barnes, who had been a friend and mentor. Moreover, Hardy called his novels the Wessex Novels, after one of the kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon Britain. He provided a map of the area, with the names of the villages and towns he coined to represent actual places. many of the poems and published them in 1898 and afterward. Back in Dorchester in 1867 while working for Hicks, he wrote a novel, The Poor Man and the Lady, which he was advised not to publish because it was too critical of Victorian society. Told to write a novel with a plot, he turned out Desperate Remedies (1871), which was unsuccessful.

![]()

Hello, Sign in

Hello, Sign in

Cart

Cart